On a recent work trip to Italy, I was able to reflect on the power of fiction and how it can so strangely morph into a pseudo-reality. With my business done in Milan, instead of flying home, I lingered an extra day and seized the opportunity to visit Verona, a quick one hour and fifteen-minute train ride from Milan.

Even in early May, the historic City Centre thoroughfares and restaurants are busy with tourists. The wonderful walk from the well preserved Roman Ampitheatre (that predates the colosseum) through the car-free streets and piazzas of the old city, across the Roman Ponte Pietra bridge spanning over the Adige River, and up many steps to the Castel San Pietro, gives a wonderful sampling of the city’s beauty.

After this light urban hike, and after wandering down various side streets, I turned onto a busy street where, a short distance away, a thick crowd assembled and lined up near an archway. Tour guides walked with their raised umbrellas or small flagpoles calling on their groups to follow. I had read up a little on Verona before arriving, and I suspected what this draw was.

As I joined the crowd, I followed a group through a short tunnel and into a courtyard equally packed with people. All cameras and phones pointed to one of two places: a small balcony on the second story of a medieval building or a bronze statue of a woman set off-centre in the courtyard.

Juliet’s House is one of the most peculiar attractions I’ve seen. Shakespeare would never have guessed just how much his play, Romeo and Juliet, would be played upon. Though Romeo and Juliet are fictional, Verona and the network of travel and tour sites promoting the city frequently reference them, even invoking their story to suggest that Verona is a romantic city for lovers: interesting given the love affair of these two didn’t turn out particularly well. Yet, people from all over the world flock here, to this place, to pay homage to love – or the story of it.

Romeo and Juliet is a classic tale. It has been told and retold with twists to maintain its relevance generation after generation. At its root, the story positions two opposing sides locked in conflict, and from each of these rivals emerges two young lovers that want to be together despite the battle or war raging around them. How often have we seen these young lovers come from feuding families, tribes, classes, races, and nations in various stories and movies? It’s a timeless theme: a relationship is threatened and often thwarted by external people and events. And here in Verona, this theme is magical, for it makes fiction real. Or maybe it’s real fiction.

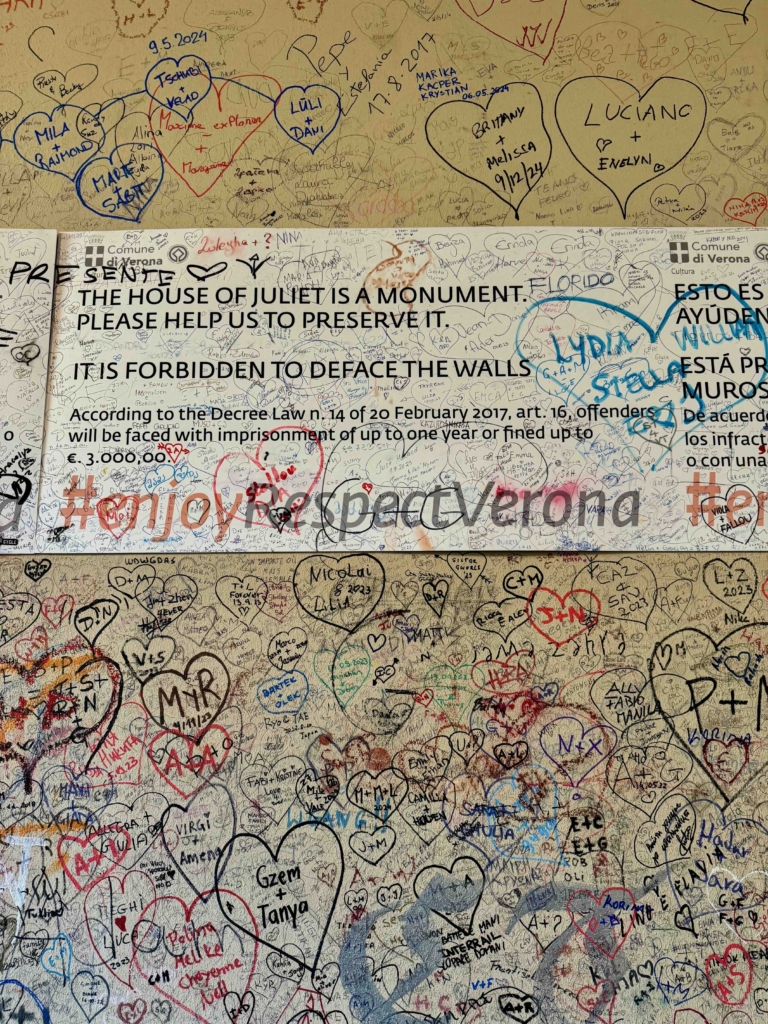

The courtyard and building that contain Juliet’s Balcony are from the medieval era. And that is about the extent of its relationship to Romeo or Juliet. The building was purchased by the city of Verona in the early 20thCentury and the balcony was added thereafter. In 1972, a bronze statue of Juliet was placed in the courtyard and quickly became a symbol of good fortune. Tourists would gather around her and rub her right breast to be lucky in love or have a favourable love life. This affectionate groping of Juliet took a toll on her body and the statue became damaged from all the wear and tear. It was moved inside the Juliet House Museum and the city paid for a replica to be made, which now stands in the courtyard today. But she is experiencing the same fate as her predecessor. So, in summary, we have a replica of an original statue that still has “love-lucky” powers, standing just below a modern balcony that Juliet never used, in a courtyard of a house that Juliet never lived in – because she never existed.

And yet – so many people come here on some strange pilgrimage to see and touch the relics of Shakespeare’s Juliet. Sure, many are herded here by tour groups, but many others, me included, are here of our own volition. I eavesdrop in on the tour guides and none of them attempt to conceal the truth from their groups: this is all fiction. Nevertheless, there is some collective desire to inject this place and these symbols with authenticity, with a real history. Or I wonder if we somehow have made Romeo and Juliet a touchstone, a metaphor or symbol, for the truth in our own romantic histories. Have many of us not experienced the all-consuming peaks of a new and fresh love, and the valleys (pits even) of despair when it ends? These characters, their dilemma, have become a stand-in for our own failed romances despite all their initial promise. There is no fiction in Romeo and Juliet’s feelings for one another. Their joy and despair we know well.

When I was doing some light research for my day trip to Verona, I came across a website for The Juliet Club (https://www.julietclub.com/en/). Every year, thousands of letters are mailed in to Juliet from tormented lovers around the world. These notes contain the secret dreams and pains of their authors as they negotiate love. If you feel you have some wisdom to impart to these star-crossed supplicants, you can become a Secretary of Juliet and respond to the letters. I, however, must abstain – it is a task for bolder souls than me.

So, as I look up to Juliet’s Balcony, I think I understand the truth of this place and what makes it real. I can imagine Juliet walking onto it to ponder the lightning strike of love after the party where she met Romeo. But I must wonder what she would think of the thronging courtyard below that doesn’t conceal a lone lover in the bushes. Rather, it hosts hundreds of former, current, and future lovers and romantics from all around the world looking back at her.

“By whose direction found’st thou this place?” Juliet asks in the play’s famous balcony scene.

“By love,” we would say. And the dream of it.