I don’t precisely know when my fascination with tombs and graves began, but I think it was on my first trip to England in 2000. I remember an overcast day (unsurprising) in the small town of Haworth. I was drawn there because of my admiration for the Bronte Sisters, and walking on the moors as well as touring the Parsonage Museum (the former family home the Brontes) seemed like the right groupie thing to do.

After my visit to the Parsonage, I wandered into the nearby graveyard. Perhaps it was the gloom of a classic cloudy English day mixed with my dark creative mood triggered by immersion in Bronte-land, but there was something wonderfully beautiful about that graveyard. Slanted or faded tombstones represented timeless perseverance and futility. Thus, a gloomy appreciation and muse was born in the resting place of the dead. I think you can see some invocation of this when the characters in my novel The Equity of Love visit the glorious Pere Lachaise.

Over the years, I’ve become a bit of a graveyard chaser (even though they are standing quite still). There is something about these strange environs of solitary peace that stir contemplation and reflection. It’s hard not to be moved, to consider your own mortality, to wonder how many years it will be before not one person comes to visit you, and to think about your lasting imprint on the world (or absence thereof). And it is hard not to be humbled.

Despite many visits to London, England in the past, I was never able to venture to Highgate Cemetery until this year. Inspired by Paris’ Pere Lachaise and built in the mid-nineteenth century, Highgate was to be the resting place for the well-to-do and fashionable of the great British metropolis.

Arriving in the morning, I paid a hefty entry fee for my ticket. Yes, this is a pay-to-enter cemetery. Highgate was a private business when first established, and it made healthy profits at the outset as people in London scrambled to pay for the best lots of eternal rest in the city. But by the 20th century, death spending became a bit out of fashion. The grand, ornate, and majestic mausoleums and tombstones were no longer in demand.

Yet, what really created the problem for Highgate was the business model itself. Cemeteries have considerable maintenance costs to keep them tranquil and peaceful spaces: there is always ongoing grave maintenance, restoration, landscaping, and gardening to be done. As the initial plots were bought in perpetuity, one-time and up-front payments looked promising, but they didn’t account for long-term operating costs. The only way to maintain steady revenue was to sell more plots – and space was finite. Over the years, the cost of operating the cemetery proved too great and Highgate declared bankruptcy in 1960.

At this point, it suffered considerable neglect. Nature and time began to do their work: the paths became overgrown; tree roots sprawled and cracked walks and gravestones, and the tombs fell into disrepair. After many years of languishing, The Friends of Highgate Cemetery Trust was formed to revitalize the cemetery and keep it for the future. Thus, I didn’t mourn parting with £10 knowing that I am keeping the place alive a little longer. It’s worth it.

From the beautifully haunting mausoleums on Egyptian Avenue and Lebanon Circle, to Karl Marx’s great communist tomb (complete with flowers and people leaving currency prominently featuring Chairman Mao Zedong), and from the grave of the writer Douglas Adams adorned with pens (of Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy fame), to the more subtle but elegant stone of George Elliot (who can forget Edward Casaubon in Middlemarch and his quest for the key to all mythologies – something I always feel Northrop Frye finished for him), this is a wonderful place for a stroll to remind you of where we are all equalized.

Christina Rosetti, the Victorian poet, along with members of her family have a plot here too. Interestingly, her brother, Dante Gabriel Rosetti (also a poet and artist) had his first wife (Elizabeth Siddal) buried in the family grave. In a forlorn romantic gesture, Dante had a notebook of poems he had written placed in the coffin with his wife when he buried her – a testament to his melancholic and anguished soul. This anguish, however, lasted for 7 years, and then he decided he wanted the notebook back (I guess he thought there were some good ideas in it). So, he obtained permission from the government to disinter the coffin and retrieve the notebook. The book wasn’t in the best of shape, but he was able to use it and rework some of the poems and later publish them. I think there’s a couple of lessons here for modern relationships: 1) No matter how bad the separation/breakup – you can bounce back; 2) There’s no shame in taking your things back from your ex, even if they’re deceased. Dante must have felt a bit sheepish about the whole affair, for he would later state he didn’t want to be buried in Highgate Cemetery. He wasn’t.

I am reminded of a poem that circulates often at funerals: “The Dash” by Linda Ellis. The dash between the two dates listed on a tombstone is where life is lived. And the poem implores us to live life well and fully with an eye to the things that matter. This is a powerful message most keenly felt when walking amongst the deceased. And although there are some prestigious people buried in Highgate, most graves are of common folk who have no biographies written about them and who are forgotten save for a dash that is empty of meaning except to those that knew them intimately in life.

* * *

Dashes, however, can be filled in with fictions, stories, and speculations. I bring you now back to my hometown of Cambridge, Ontario. In my novel The Equity of Love, the patriarch James Hardich is buried in Mount View Cemetery in old Galt. In some handwritten notes I have now lost, I had a chapter of the Hardich family visiting James’ tombstone. This scene described the cemetery, but I discovered that it was more of a vehicle to share some personal preference for the place (my father is housed in a columbarium here) and to share some local lore that did not advance my story. So, I never typed it into my drafts. Now, however, I will share a small tidbit of Cambridge history with you.

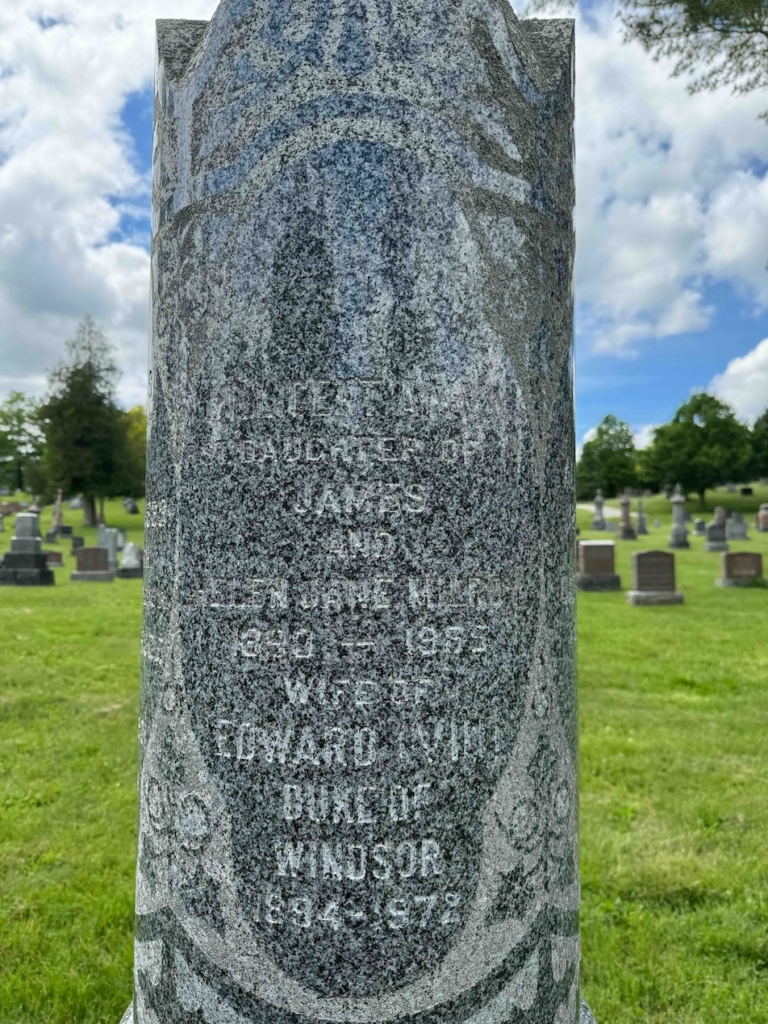

In the cemetery is a large cylindrical gravestone inscribed with the family name Milroy. Although tall and ornate, there are plenty other tombstones that surround the graveyard of equivalent size and decoration. But this stone has one of the most unique epithets in all of Ontario. Etched onto one of the sides is the following:

Millicent A.M.M.M. P.St.

Daughter of

James

and

Helen Jane Milroy

1890 – 1985

Wife of

Edward (VIII)

Duke of

Windsor

1894-1972

Yes, Millicent Milroy was wife of the Duke of Windsor – or rather, she claimed to be. Note the assertion is entirely her own.

Millicent was a schoolteacher and resident of the area, eventually dying in Guelph, Ontario a short distance away. Her version of events was that she met the Duke on his Canadian tour in 1919. The Duke came to visit Galt (Cambridge) that very year, along with Guelph, Toronto, and other stops. He would return to Canada a few more times too, and he had a fondness for the western province of Alberta where he bought a ranch. Interestingly, Millicent did say that she married the Duke secretly out West.

Edward VIII was well known for his romantic dalliances with women and was the iconic Playboy prince. And much has been made of certain diary entries by Canadian Prime Minister Mackenzie King where he notes that the Duke confided to him that he had fallen in love with a Canadian woman. But beyond that and some coincidental evidence, there really isn’t much support for this rumoured romance, let alone wedding. Belief in Millicent’s claims tend to be one of those instances of “if it cannot be disproved, it could be true.”

I think what is often overlooked in the discussion is Millicent’s penchant for spinning connections to royalty. The first line of epithet is “Millicent A.M.M.M. P.St.” Those initials have been suggested to mean Agnes Mary Maureen Marguerite, Princess of the Royal House of Stuart. Thus, setting aside her story of marriage to Edward VIII, she also believed (or made it known) that she was of royal stock.

One event that lends a mysterious credence to Millicent’s royal marriage for believers of her tale is that when she died, her house was broken into and a wood box containing all the “proof” of her claims was stolen (including royal mail etc). This was obviously seen as a great coverup to hide the evidence.

In the end, whether Millicent’s claims are true or not (and I do not believe they are), it doesn’t detract from a piece if interesting Cambridge lore. Enduring fascination of the story led to the authoring of a play called Queen Milli of Galt that has been performed across Canada. And this is what I find most fascinating: the catchiness of the play’s title has given the story a new life and I recently heard people referring to the grave as “Queen Milli’s.”

One thing we do know for certain: Millicent’s claims were never made for money or to elevate her public position. She remained quite private with the exception of her very public statement on the tombstone. And she maintained that the truth (and proof) of her claims would be revealed upon her death.

Although nothing has been revealed to validate her story, I think she has more popularity now than ever. Afterall, in life she was a schoolteacher, then the woman who claimed to be wife to a Duke – but in death she is now Queen Milli. That’s quite a title climb.

Rest in peace Queen Milli.

Note: Growing up in Cambridge, I have long been familiar with the tale. But in my research of Millicent Milroy, I found the most comprehensive summary of her life and story to be: https://ithappenedincambridge.com/millicent-milroy-1. Read there for an investigative journalism type piece.