A nine-hour drive west of Cairo, and a mere 50 kilometres from the Libyan border, is Siwa Oasis. Even today, its remoteness makes it a bit of trek to get to, though tour busses are becoming more frequent in the area. This isolation in the great Sand Sea of the Sahara Dessert has been woven into the history of the Oasis and shaped its destiny as much as its inhabitants have.

Siwa is an outsider to traditional Ancient Egyptian history because of its distance from the main epicentre of Egyptian power consolidated along the Nile River. Siwa’s connection to Egypt is really only evidenced from the 26th Dynasty of Pharaohs (~7th century BC) and onward. By this time, the Ancient Egyptian empire was in decline. 2,500 years of native Egyptian rule had ended with the conquests of Egypt by different kingdoms and rulers: the Libyans to the west, the Kushites/Nubians to the south, the Persians to the east, and eventually the Greeks to the north.

The exact events that led to the fame of Siwa Oasis are not known, but by 600 BC, Siwa had a Necropolis and a Temple dedicated to the Egyptian god, Amun. Moreover, the Oracle of Siwa at the Temple, a person acting as a link to the gods with prophetic ability, was known and revered throughout the Mediterranean.

On a 3-night stay in Siwa in November of 2023, my wife and I leave our ecolodge right after breakfast one morning to visit the Necropolis. The excursion we arranged with the hotel comes with a local Siwa guide to escort us and share the history and stories of the place. Our guide is pleasant and solicitous, and his English is good.

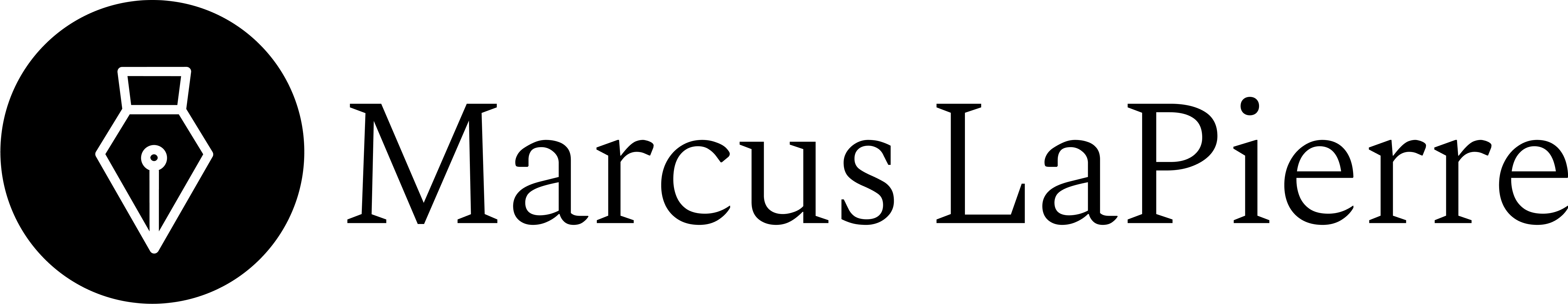

The Necropolis is known as Gebel al-Mawta (or Mountain of the Dead). It’s more of a large rocky hill with steep edges than a mountain. As we ascend it, the first thing that catches my eye is the pot-marked ground and the hundreds of small caves burrowed into the rockface. These are the tombs that would have housed thousands of bodies, but most are barren now and closed to the public for safety reasons. From the 26th Dynasty through to Greco-Roman Egypt, the Siwan people buried their dead here. The majority of tombs are not well preserved: over the centuries, the local population removed items of value from the caves and would sometimes use the tombs for shelter or as temporary dwellings. There are a few famous tombs, however, that escaped this casual damage. And to one of these we are directed.

There are only a couple of other small groups of visitors touring the mountain, and always at a distance from us – there are no lines, no crowding. The place is wonderfully quiet and intimate: appropriate given that we are in a desert graveyard. Surrounding the mountain are the date-palm farms that Siwa is famous for, and in the distance one can see the town of Siwa and the ruins of the Shali fortress. It’s jarringly peaceful and quiet after the crowds of Cairo and the unceasing honking of horns there.

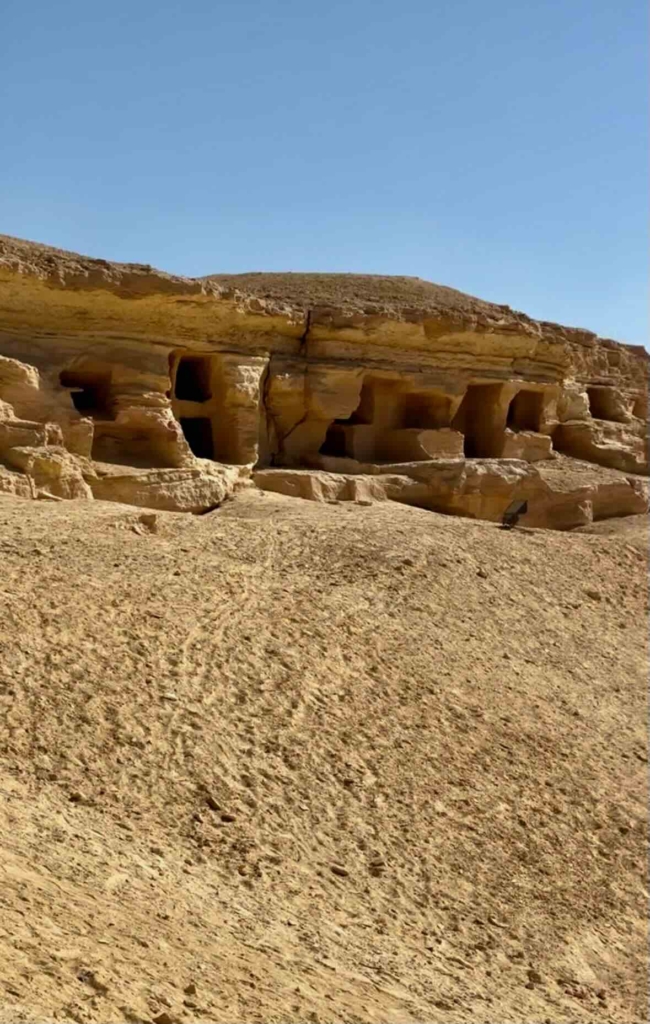

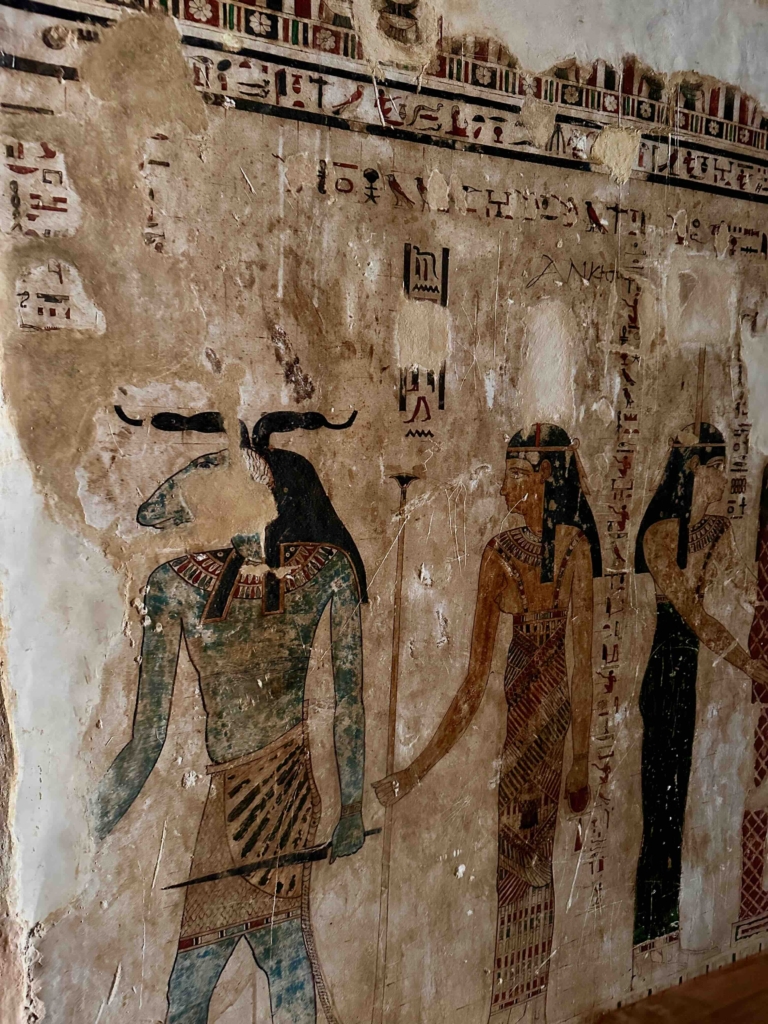

When we reach a particular opening into the mountainside, the guide explains that this is the tomb of Si-Amum. What makes it exceptional is the damaged, but still preserved, paintings on the walls. After thousands of years, some of the images are still clear and have retained their colour. Not much is definitively known about Si-Amum, but he seems to have been wealthy enough to secure such an adorned burial chamber. His likeness is depicted on the wall with black hair and a beard. There is a thought that his background was Greek, but that he had adopted the customs and religion of the Egyptians.

As we study the walls and the paintings, our guide points out different figures: the goddess Nut, Osiris and others. My wife is drawn to the image of a boat on a river with three people on it. She asks the guide what it means.

The guide looks at it briefly. “It’s the movement of the religions. Each flows into the other. It starts with the Egyptian gods on the left, then to the Christian Copts in the middle – you can see the cross. Then to Islam. You see the stars? That is Islam,” he says.

My wife gives me the quickest of looks that two people share when they hear something that isn’t right. We have Egyptian friends; even we know that the cross the guide points to is the Ankh with its droplet top. For Ancient Egyptians, it was a symbol of eternal life and often represented the Nile or the key to the Nile. And though we did not know it at the time, we would later learn on our trip down the Nile visiting temples that that the stars represent the god Nut or the afterlife.

“What is the date of these paintings?” I ask.

“100 BC to 200 BC,” the guide replies, confidently.

“How is it possible that the paintings have the other religions?” my wife asks. “Christianity and Islam weren’t around then.”

I wait for him to provide a historically valid reason for this. Perhaps he will say the tomb paintings were first done in 200 BC, but that the chamber was re-opened at various times and other paintings added or updated. Or maybe the image of the boat is modern graffiti set to look ancient. But no, he provides none of these explanations.

“They knew what would come. Like prophecy. Magic,” he says. There is no stumble or uncertainty in his response. He is in earnest.

This seemed like such a tale to me, I wait a full minute for him to acknowledge the joke and let us in on it. But he maintains his pleasant manner with no hint of a smile.

My wife gives me that look again. Amused, we are content to go along with our guide’s proposition. He certainly has knowledge in other areas, so what if wall art isn’t his thing? I am curious about his invocation of the word magic as an acceptable explanation or excuse for anything. Perhaps I wouldn’t have thought more of it, but it comes up again when the guide talks about the Mountain of the Dead and the old magic in Siwa. He retains his usual earnestness.

We return to our lodgings for lunch. In a small palm grove, an oasis within an oasis, we eat and lie on comfortable mattresses poolside. There are times when the beauty of a scene is not conducive to conversation between my wife and I – and this is one of them. Silence is the currency of respect and gratitude to the desert, the mountain, the sky and the water. But my wife cannot resist calling out what is on the tip of my own tongue. “Magic,” she says. There is, indeed, a spell cast here.

In the afternoon, we have another excursion with a different guide. We drive in the jeep through town and along rough roads to the Temple of Amun. The journey there is its own wonderful experience. I marvel at the young boys we pass – they must be 12 years old – driving 3-wheel cargo motorcycles with brothers and sisters in the back flatbed. Other boys drive carts pulled by donkeys carrying produce and supplies. Though modernity is coming, the young don’t have video game systems and cell phones yet, so their lives and responsibilities are radically different than their age counterparts in Canada.

We chat with our new guide about Siwa and its people. He opens up about how Siwa is different now. Money from the outside brings good and ill – opportunity and social mobility, but also drugs and alcohol. The young are seeing more of what is outside Siwa and in the big cities. Yet, he proudly talks of Siwa’s history, and how there is still much of the past that is carried into the present.

I am not sure how it comes up so suddenly, but he mentions magic – black magic. When my wife lightly presses him to describe it, the guide alludes to how it is still around Siwa. He tells us a story of how one of his friends had a curse put upon him by a neighbour and how horrible his life became. I wish I could tell the tale here, but I feel it was given to us in confidence, and it would seem a betrayal for me to share it. Nevertheless, the guide was as sure of the existence of magic as the heat of the sun or the salt in the lakes of Siwa.

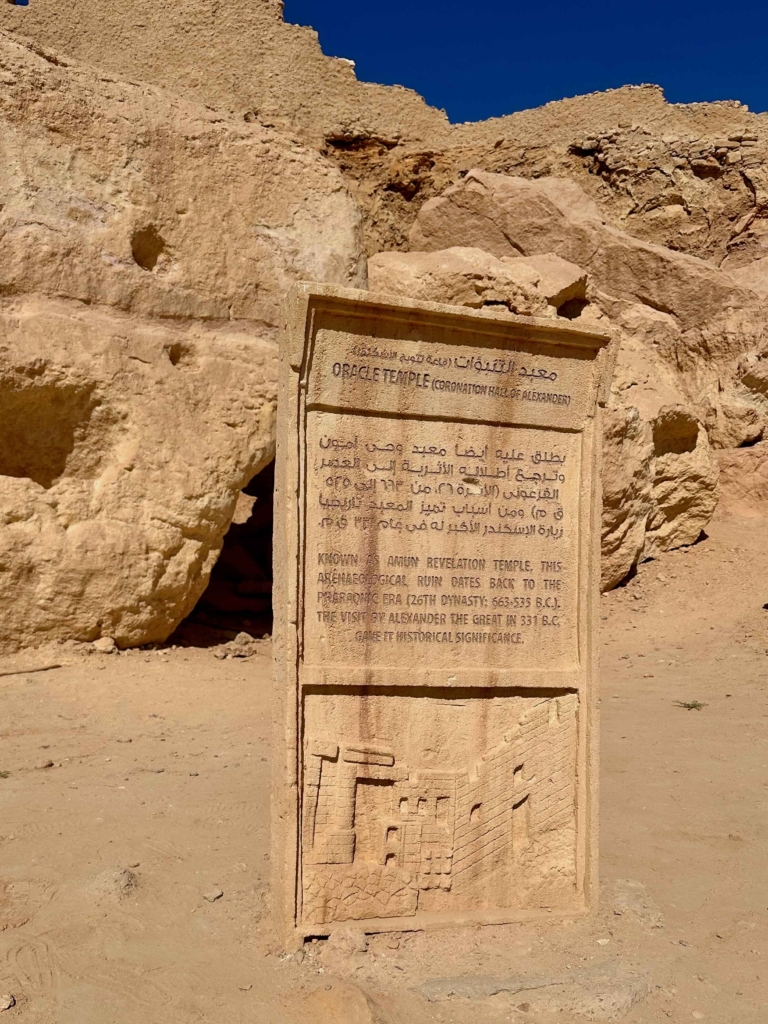

At the Temple of Amun, we enter ruins. Unlike many of the ancient sites in Cairo or Luxor along the Nile, this isn’t well preserved. It was once a large temple complex so famous that Alexander the Great would travel here after establishing the city of Alexandria on the Mediterranean in northern Egypt. Alexander’s journey was fraught with some misadventures in the desert where his party became lost and ran out of water, and only through divine intervention did he arrive at the Oasis to consult with the Oracle. The historical sources have different interpretations of what was discussed between Alexander and the Oracle: one says only that there was a meeting and that Alexander was pleased with it; another says Alexander was declared the son of the god Amun, and therefore the pharaoh and rightful ruler of Egypt; still, another says that Alexander learned that all his father’s murderers were punished and that the world was his to conquer. Whatever actually happened in that meeting, we can likely surmise Alexander’s trip to Siwa was a political excursion to achieve legitimacy in Egypt.

One must imagine the grandeur of the place that once stood here, for only a rocky shell remains. A fully intact building is near the entrance, but it is an old mosque being restored that was built on the Temple grounds. The rest of the Temple is roofless rooms and half-walled chambers filled in by the storytelling of our guide, who describes where the Oracle would have granted an audience to visitors and the ritualistic cleansing visitors performed before the meeting.

I am beginning to feel something in the air, perhaps a spell casting again. I am aware that I am in an extraordinary and special place. For hundreds of years, people with the gift of foretelling walked these grounds. Were they charlatans and hustlers or did they have some special and prophetic wisdom? Even this question shows my mind slowly opening to possibilities. For, back home, I find talk of psychics or any modern-day preachers of special powers insufferable – in fact, I can barely tolerate the claims made by famous companies and brands in commercials or online ads.

I would think about magic for the remainder of my trip in Egypt. I wouldn’t say it was an intrusive preoccupation, but a steady rumination. There is something about this ancient land that does make one contemplate great mysteries: the supernatural, death, rebirth and the afterlife. These concepts surround you as you move through the temple complexes at Luxor, Edfu, Kom Ombo, and Philae. The intricate symbols of the gods and their interactions with each other and the pharaohs are inscribed on columns, walls, and holy rooms in hieroglyphs and art everywhere. On one or two occasions, I would run my finger lightly over some hieroglyphs on a temple wall and wonder if something might happen (to my knowledge nothing did, but perhaps there is a delayed effect). There is magic here, a connection to something old and grand and mysterious. This is probably why Egypt, and its history, are so ripe for theories of aliens, secret religious societies, mystics, and advanced civilizations whose accomplishments dwarf our own.

As I became open to this magic in Egypt, I also became aware of how closed I have been to it in recent travels over the last few years.

In my book, The Equity of Love, one of the characters gives insight into that newness that has long made travel almost a spiritual journey:

“The city was beautiful, and he felt the enchantment that is only known to the traveler, the visitor, the guest. Removed from his familiar surroundings, he found pleasure in the everyday of a new place. People and their interactions were all accentuated against the backdrop of five-story nineteenth-century buildings, old churches, and cafe-lined streets. The cars were different, the air was different, the sounds of speech were different. He was watching, smelling, and hearing it all. Wondering. Thinking. Analyzing.”

So, what I was experiencing was this contemplation of the divine again afforded by the unfamiliar. And yes, I must stress that word unfamiliar. Because it is not lost on me that this complex and mysterious religious symbology in Egyptian art, sculpture, and words exists in the great Christian churches too. Yet, I have grown somewhat numb to it over time. I remember my first trips to the United Kingdom and Europe many years ago and entering the cathedrals of St. Paul, Canterbury, Notre Dame, and the Nativity of St Mary. I was fascinated by the elaborate puzzles of some of the art and the stories they depicted. Whether a fresco, a painting in a chapel or a solitary statue one walks past in the church aisle, these are often steeped in a system of codes and references that only a person with an understanding of church history, the bible, and the tales of hundreds of saints could understand (or you had a guidebook like me). The miracles, the mystical, the magical, are everywhere.

But the enemy of awe is the familiar. And over the years, as I have visited more churches, my connection to the mystical has wavered: my mind – or my heart – has not been open to it. My appreciation of these magnificent buildings seems to have shifted to a fully secular lens. I have come to assess these churches in their historical and architectural context, losing sight of the mystery within, and what it meant to the parishioners over the centuries. How odd is it that I came to Ancient Egypt to realize this? I think I needed to experience the presence of awe again to know that it has been absent. I need to reawaken that mystery and magic that exists in some of those more familiar, but still wonderful, churches. In such a foreign place as Egypt, it is easy to rediscover wonder.

Egypt, indeed, has magic. It is mystical and mysterious. It is a place that is awful – yes, awful. I mean it in the sense of that original word, not the slang and new meaning that has replaced it. Awful: full of awe, inspiring wonder.

In the last 15 to 20 years, Siwa has really started to focus on developing its tourism industry both within Egypt and abroad. And, as with any isolated place that experiences investment, economic growth and tourism, it is changing. It feels like the Siwans are leaving some prelapsarian state as the modern world encroaches on them. But this has always been the way: the same might have been said when the Greeks came, or the Romans, or the Berbers, or later still, King Muhammad Ali – the founder of Modern Egypt. Still, despite all of these outside influences, Siwa’s connection to the Ancient Egyptians and to magic persists.

There may come a time when magic at Siwa (and Egypt) runs out, when it no longer inspires awe. But for now, there is an abundance of it. And I am grateful to my guides who, in casual statements, reminded me to reconnect with the magic that is always around me on my travels and in the places I have been blessed to see.